Silkroad Nedstängd av FBI

2013-10-03

How the feds took down the Dread Pirate Roberts

What he wouldn’t give for a holocaust cloak.

by Nate Anderson and Cyrus Farivar Oct 3 2013, 6:00am CEST

Källa: https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2013/10/how-the-feds-took-down-the-dread-pirate-roberts

Aurich Lawson

THE SILK ROAD BUST

- Feds: Silk Road boss paid $80,000 for snitch’s torture and murder

- FBI: Silk Road mastermind couldn’t even keephimself anonymous online

- Feds shut down Silk Road, arrest alleged admin Dread Pirate Roberts

View all…

The Dread Pirate Roberts, head of the most brazen drug trafficking site in the world, was a walking contradiction. Though the government says he raked in $80 million in commissions from running Silk Road, he allegedly lived under a false name in one bedroom of a San Francisco home that he shared with two other guys and for which he paid $1,000 a month in cash. Though his alleged alter ego penned manifestos about ending “violence, coercion, and all forms of force,” the FBI claims that he tried to arrange a hit on someone who had blackmailed him. And though he ran a site widely assumed to be under investigation by some of the most powerful agencies in the US government, the Dread Pirate Robert appears to have been remarkably sloppy—so sloppy that the government finally put a name to the peg leg: Ross William Ulbricht.

Yesterday, Ulbricht left his apartment to visit the Glen Park branch of the San Francisco Public Library in the southern part of the city. Library staff did not recognize him as a regular library patron, but they thought nothing of his visit as he set up his laptop in the science fiction section of the stacks. Then, at 3:15pm, staffers heard a “crashing sound” from the sci-fi collection and went to investigate, worried that a patron had fallen. Instead, library communications director Michelle Jeffers tells us that the staff came upon “six to eight” FBI agents arresting Ulbricht and seizing his laptop. The agents had tailed him, waiting for the 29-year old to open his computer and enter his passwords before swooping in. They marched him out of the library without incident.

For a promising young physics student from Austin, Texas, this wasn’t how things were supposed to turn out.

Ulbricht, in happier times.

“Choose freedom over tyranny”

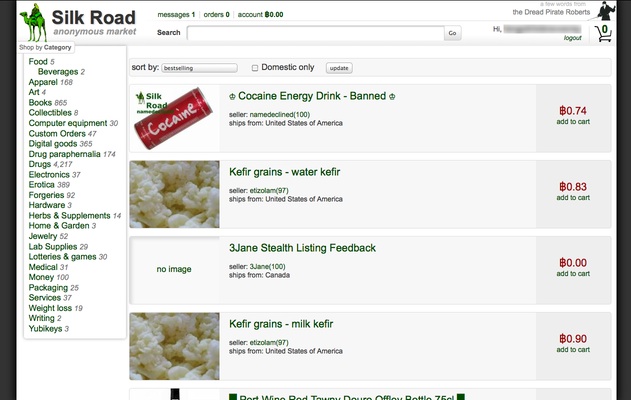

Sure, you could buy meth, LSD, cannabis, heroin, and MDMA on the Silk Road, but the hidden website wasn’t (just) about drugs. Silk Road was, said its owner, about freedom. In January 2012, as part of a “State of the Road Address” posted in the site’s discussion forum, the Dread Pirate Roberts explained the site’s goal: “To grow into a force to be reckoned with that can challenge the powers that be and at last give people the option to choose freedom over tyranny.”

To that end, the Dread Pirate Roberts built the Silk Road marketplace in 2011 as a “hidden” service accessible only over the encrypted Tor network. To connect, users first had to install a Tor client and then visit a series of arcane site names (the most recent was silkroadfb5piz3r.onion), but the reward was a simple, effective marketplace to buy drugs from sellers all over the world using such Internet commerce staples as escrow accounts and buyer feedback. The product was shipped through the mail, direct from seller to buyer, keeping the Dread Pirate Roberts clean. The only link between him and the drugs was the money, and Roberts eventually took only the electronic currency called Bitcoin to make this hard to trace. He even ran a program called a “tumbler” to route incoming Bitcoin payments through a complicated series of dummy transactions, so as to make them infeasible to trace through the public Bitcoin blockchain. Out of each transaction, Roberts took a cut—8 to 15 percent, depending on the size of the sale.

This eventually earned Roberts a pirate’s treasure. By 2013, Silk Road had nearly one million user accounts. In the 2.5 years the site operated, it facilitated 1.2 million transactions worth 9.5 million Bitcoins—or about $1.2 billion in total money exchanged. (Bitcoin values varied widely over this period.) Roberts picked up a cool $80 million in commissions.

No surprise, then, that the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Internal Revenue Service, Homeland Security Investigations, and the FBI all joined forces to track down Roberts and the largest sellers on his marketplace. In November 2011, after coming under pressure from Congress, the agencies began the hunt and quickly found that Roberts had been right—encryption, Tor, and “tumbled” Bitcoins were a potent combination to crack.

Ulbricht at his 21st birthday party.

But investigations always have many threads to pull. The feds couldn’t initially follow the money to Roberts, nor could they find the physical location of his cloaked servers. In the absence of usual digital clues, the feds fell back on a low-tech approach: keep going back in time until you find the first guy to ever talk about the Silk Road. Find that guy and you probably have a person of interest, if not Roberts himself.

So they looked, assigning one agent to conduct “an extensive search of the Internet,” in the FBI’s words, looking for early Silk Road publicity. The earliest post ever to mention the site appeared on a drug-oriented forum called shroomery.org, where a user named “altoid” had made a single post. It read:

I came across this website called Silk Road. It’s a Tor hidden service that claims to allow you to buy and sell anything online anonymously. I’m thinking of buying off it, but wanted to see if anyone here had heard of it and could recommend it.

The post directed readers to visit silkroad420.wordpress.com, belonging to the blogging operator WordPress, where further instructions would be found for accessing the real Silk Road site. A subpoena to WordPress Revealed that the blog had been set up on January 23, only four days before the Altoid post. If this wasn’t the first mention of Silk Road, it was certainly one of them.

Altoid became a person of interest, but who was he? Further research revealed that Altoid had been posting on a board called Bitcoin Talk—further suggesting a possible link to the Silk Road, which operated on Bitcoin. A key break came when the agent found an October 11, 2011 post by Altoid, looking for an “IT pro in the Bitcoin community” and directing all inquiries to “rossulbricht at gmail dot com.”

A subpoena to Google revealed that this account was in fact registered to one “Ross Ulbricht.” The account was also linked to a Google+ profile, which had a picture of Ulbricht and a link to his favorite videos on YouTube. The videos provided a key clue; several of them were from the libertarian Mises Institute, whose views jibed with the leanings of the Dread Pirate Roberts. In addition, Roberts had repeatedly linked up Mises videos when posting in the Silk Road forum and had referenced “Austrian school” economists like Ludwig von Mises, for whom the Institute was named. The clue was suggestive but not conclusive.

Still, the pieces were coming together.

The economic simulator

Ulbricht and his horseshoe mustache.

With the name Ross Ulbricht, the feds went to other social networks. They found Ulbricht on LinkedIn, where he talked about his dissatisfaction with the physics work he had been doing as a graduate student at Penn State. “Now, my goals have shifted,” Ulbricht wrote. “I want to use economic theory as a means to abolish the use of coercion and aggression amongst mankind… The most widespread and systemic use of force is amongst institutions and governments, so this is my current point of effort. The best way to change a government is to change the minds of the governed, however. To that end, I am creating an economic simulation to give people a first-hand experience of what it would be like to live in a world without the systemic use of force.”

Could the “economic simulation” be, in fact, Silk Road? One tantalizing hint comes from ananonymous article published in alternative newspaper The Austin Cut, located in Austin, Texas where Ulbricht grew up. The story was, in essence, a primer on how to build Silk Road and an explanation of what made the site so amazing—and the answers were “freedom” and “lack of force.”

“Hackers, anarchists, and criminals have been dreaming about these days since forever,” wrote the author. “Where you can turn on your computer, browse the web anonymously, make an untraceable cash-like transaction, and have a product in your hands, regardless of what any government or authority decides… This is about real freedom. Freedom from violence, from arbitrary morals and law, from corrupt centralized authorities, and from centralization altogether. While Silk Road and Bitcoin may fade or be crushed by their enemies, we’ve seen what free, leaderless systems can do. You can only chop off so many heads.”

The article’s author then relayed a telling anecdote from Silk Road, one in which people began arguing over a botched deal. They got angry; one threatened violence, but he was simply mocked by other users because he had no way to find his target. “It showed how successful Silk Road really is,” wrote the author. “It makes drug buying and selling so smooth that it’s easy to forget what kinds of violent fuckers drug dealers can be. That’s the whole point of Silk Road. It totally takes evil pieces of shit out of the drug equation. Whether they’re vicious drug dealers or bloodthirsty narcotics cops, both sides of that coin suck and end pretty much the same way. Death, despair, madness, prison, etc. Thanks to decentralization and powerful encryption, we’re able to operate in a digital world that is almost free from prohibition and the violence it causes.”

This fits with Ulbricht’s arguments, and the piece might well be by him, providing a better sense of why he saw the experiment as such an important one. We asked the editor of the Cut what he thought. “I wondered the same thing,” he said, but added that he did not know who wrote the piece.

In any event, the feds had a name but no hard evidence linking Ulbricht to the site management. They knew that Ulbricht had moved to San Francisco and was staying for some time with a friend, and they knew that whoever was logging into the “rossulbricht” Gmail account was doing it on occasion from the friend’s house. But the next link in the chain only came when the feds uncovered a post on the popular coding advice site StackOverflow.

In early 2012, Ulbricht registered a StackOverflow account using his Gmail address; the username was “Ross Ulbricht.” On March 16, Ulbricht asked for help with connecting “to a Tor hidden server using curl in php.” He included several lines of code that weren’t working quite right. Perhaps realizing that this was a bad idea, one minute later Ulbricht changed his username to “frosty” (he changed his e-mail address a bit later), but he had already revealed his interest in running Tor sites.

At this point, the government gets cryptic. On July 10, 2013, Customs and Border Protection intercepted a package coming from Canada into the US as part of a “routine border search.” This package contained nine counterfeit IDs, each of them in a different name, but each of them showing a picture of Ulbricht. They were addressed to his San Francisco address.

Two weeks later, the government found the Silk Road servers in various foreign countries, though it won’t say how. (The FBI gives no indication that Tor was compromised in this case, though given that the agency has recently found ways to spy on Tor users, it’s hard to absolutely rule out the possibility.) It’s possible that finding various aliases for Ulbricht enabled agents to track the money used to pay for the servers, but the events may have been unrelated. The main Silk Road Web server was found in “a certain foreign country” that has a Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty with the US. Under the terms of that treaty, the government asked for an image of the server’s hard drives, which was made on July 23 and then turned over to the FBI.

(Update: Computer security research Nicholas Weaver speculates that “the FBI (with a warrant) hacked the site sufficient to discover the site’s IP by generating a non-Tor phone-home, and then contacted the country of the hosting provider which then got the server imaged. Yet since the server imaging didn’t involve taking the server down or disrupting service sufficient to spook Mr DPR into taking his bitcoins and running, I suspect that this was some virtual-machine hosting provider.” But at this point, no one knows.)

Three days later, agents from Homeland Security Investigations visited Ulbricht’s 15th Street home in San Francisco. They found him at home, where his two housemates knew him as “Josh.” One of them told the agents that “Josh” was “always home in his room on the computer.” As for Ulbricht himself, he refused to answer most questions, though he did volunteer one curious bit of information, apparently as a way of indicating that such documents could be obtained so easily that anyone might have ordered them, or that he had been framed.

“Hypothetically,” he told the agents, anyone could visit a site named “Silk Road” on “Tor” and order any drugs or fake IDs they wanted.

“I wouldn’t mind if he was executed”

“I wouldn’t mind if he was executed”

While this was going on, the FBI was tearing into the mirrored server, where it found all sorts of incriminating information. For one thing, the server had been set up to accept encrypted SSH logins, and the server’s public key ended with “frosty@frosty.” In addition, a lightly modified version of the code posted to StackOverflow was being used on the server—apparently with its errors corrected. Private messages from the Silk Road forums showed that Dread Pirate Roberts had mentioned his interest in acquiring fake identification documents during the month before Ulbricht’s own fake IDs had been seized at the border.

But in the private forum messages, the feds found something even worse: an alleged murder-for-hire scheme.

This is the point at which an already-crazy story runs right off the rails and into the ditch, because not only did Roberts want someone killed—he didn’t know enough about what he was doing to make sure it happened. Indeed, it certainly looks like the Dread Pirate got bilked out of $150,000.

On March 13, 2013 Roberts was approached through Silk Road’s private messaging feature by “friendlychemist,” who failed to live up to his nickname and instead tried to extort Roberts. Friendlychemist had, he said, hacked into one of the computers of a major Silk Road dealer and obtained information on buyers, information he would release to the world unless Roberts paid up. And who would use Silk Road if it wasn’t secure?

Friendlychemist needed $500,000, he said, to pay off his own drug suppliers, with whom he had fallen behind. On March 20, Roberts wrote Friendlychemist, asking to be put in touch with these suppliers. Someone named “Redandwhite” messaged him on March 25, saying, “I was asked to contact you. We are the people Friendlychemist owes money to. What did you want to talk to us about?”

Roberts tried to convince Redandwhite to start doing business on Silk Road but then added on March 27, “In my eyes, Friendlychemist is a liability and I wouldn’t mind if he was executed.” Roberts then provided an address in White Rock, British Columbia, where Friendlychemist allegedly lived with his “wife + 3 kids.” When Friendlychemist threatened to release his information within 72 hours if he wasn’t paid, Roberts went back to Redandwhite, asking “I would like to put a bounty on his head if it’s not too much trouble for you. What would be an adequate amount to motivate you to find him?”

The story then went full-on Breaking Bad nuts, with Redandwhite demanding $150,000 for a “non-clean” kill and $300,000 for a “clean” version. Roberts said that he knew the value of such things; he claimed to have paid $80,000 for a previous “clean” hit, and he wanted a discount.

Did I say earlier that the story had already gone off the rails into Crazytown? Reader—I was wrong. Because a federal indictment unsealed separately today in a Maryland court says that Roberts had in fact arranged such an $80,000 hit just a few weeks earlier. Not crazy enough? Turns out that the “hitman” in this first attempt was actually a federal agent.

Roberts was upset that one of his employees—records show these employees were paid between $1,000 and $2,000 a week—had stolen from Roberts and eventually managed to get himself arrested by dealing with an undercover agent. Roberts wanted the employee tortured so that he would return the missing Bitcoins. Not knowing much about hitmen, Roberts ended up talking to the very undercover agent who had helped bust his employee.

On January 26, 2013, Roberts asked that the former employee get “beat up, then forced to send the bitcoins he stole back.” A day later, afraid that his former employee would squeal to the police, Roberts asked if it was possible to “change the order to execute rather than torture?” Roberts said he had “never killed a man or had one killed before, but it is the right move in this case.” The agent offered to do the job for $80,000.

The agent was actually paid a $40,000 advance from an Australian bank account. He soon provided the “proof of death” Roberts wanted, first feeding Roberts an elaborate story about assassins and how the employee was “still alive but being tortured” and then later sending staged photos of the alleged torture. Roberts said he was “a little disturbed… I’m new to this kind of thing.” The agent then said the employee had died of a heart problem under torture, and he sent along a fake picture of the “dead man.”

“I’m pissed I had to kill him… but what’s done is done,” Roberts replied. “I just can’t believe he was so stupid… I just wish more people had some integrity.” On March 1, Roberts wired the second $40,000 to the undercover agent.

Fast forward two weeks and Roberts, who believed he had just killed a man, was ready to do it a second time—but he didn’t understand why he had to pay so much. The two sides agreed on $150,000, and Roberts provided a sequence of random numbers, meant to be written on a card that would be placed next to Friendlychemist’s dead body and photographed. Roberts’ Bitcoin transaction logs showed that he did in fact send this amount of money to Redandwhite.

On April 1, Redandwhite responded, “Your problem has been taken care of… Rest easy though, because he won’t be blackmailing anyone again.” Redandwhite apparently sent the requested photo, too, because on April 5, Roberts said that he had “received the picture and deleted it. Thank you again for your swift action.”

Bizarre and brutal—but was it real? Redandwhite does not appear to have been a federal agent, since FBI agent Christopher Tarbell—who was also involved in bringing down Hector “Sabu” Monsegur from Anonymous—called up the Canadian police to find out if a murder had really happened. According to Tarbell, the Canadians have “no record of there being any Canadian resident with the name DPR passed to Redandwhite as the target of the solicited murder-for-hire. Nor do they have any record of a homicide occurring in White Rock, British Columbia on or about March 31, 2013.” The truth of the situation remains murky, but it sounds a lot like the Dread Pirate Roberts got scammed… in two very different ways.

Setback

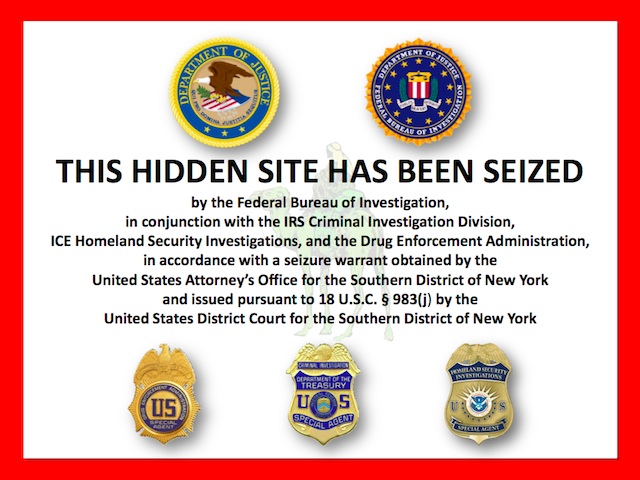

The federal seizure notice that appeared on Silk Road.

The feds arrested Ulbricht yesterday and charged him with being the Dread Pirate Roberts, they seized the Silk Road domain name, and they grabbed all the Bitcoins the site held. This particular economic experiment is now over. But the libertarianism of Dread Pirate Roberts/Ulbricht isn’t an anomaly in tech circles; indeed, it has a long pedigree, with many geeks (notably the “cypherpunks”) believing that strong cryptography and good technical design would help digital systems massively expand human freedom, even in ways that nation-states dislike or outlaw.

Perhaps the most perfect previous realization of this vision was HavenCo, the quixotic “data haven” that set up shop on a rusting World War II sea fort off the English coast as a way of evading national law in the early 2000s. Servers would use crypto so good that not even HavenCo’s operators would know what their clients were doing on the machines, and the goal was similar to Silk Road’s: freedom. The venture never attracted much more than some online gambling outfits hoping to find a safe place from which to reach countries like the US, but its romantic location and big dreams made the company a media superstar.

Ryan Lackey was the key implementor of HavenCo, and he lived aboard the fort for weeks and even months at a time, trying to turn his libertarian principles into practical reality. Ten years on from the HavenCo experiment, I asked Lackey what the Silk Road takedown meant for the movement.

“Obviously in the short run it’s a setback,” he told me, because “Silk Road was the main example of a long-running ‘hated by the government’ service which was able to use technical means to operate, profitably, with a lot of users. I can’t condone illegal activity, and it looks like Silk Road/DPR may have engaged in violent activity over and above just flouting drug laws, but Silk Road was technically a really interesting system.”

To Lackey, the best way forward for those concerned with using tech to advance human freedom is to start with something legal. “It would be a lot better to work on the technology in explicitly legal and protected areas, like ‘an anonymous way to organize political movements in the US,’ versus a drug/murder for hire market,” he adds. And what’s needed is a new generation of protocols, “asynchronous, message-based, and fully pseudonymous, with the ability for users to build reputation independent of the transport.” In Lackey’s view, no one worked hard on these problems for the last decade because “no one believed NSA/FBI/etc. would seriously go after users; that has been conclusively disproved.”

Now, with the Edward Snowden leaks and Silk Road’s demise, security and anonymity have become hot topics once again—and they may spur a renewed interest in making the ‘Net less traceable.

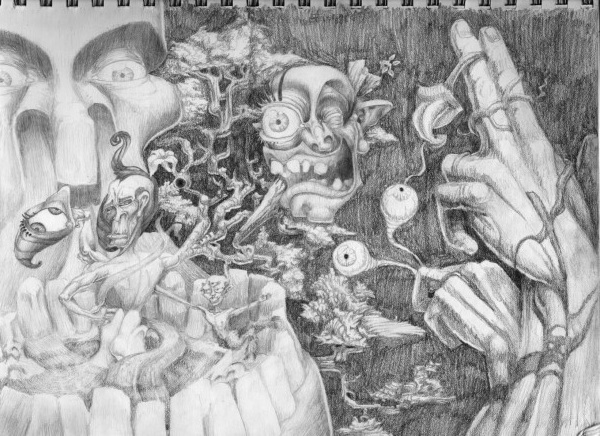

A scene from one of Ulbricht’s sketch books.

Dread pirates

René Pinnell was one of Ulbricht’s best friends. The pair knew each other since they were kids in Austin, and it was Pinnell who encouraged Ulbricht to move to San Francisco. (Pinnell appears to be the “friend” listed in the FBI complaint. You can watch Pinnell and Ulbricht chat about their upbringing in a long YouTube video.) When we spoke to Pinnell today, he was hesitant to say anything without speaking further with Ulbricht’s lawyer, but he did tell The Verge, “I don’t know how they messed it up and I don’t know how they got Ross wrapped into this, but I’m sure it’s not him.”

Who knows—nothing has yet been proven. Indeed, in an interview conducted with Forbes this summer, the (current) Dread Pirate Roberts maintained that he was not actually the creator of the Silk Road as the FBI believes. Like his namesake in The Princess Bride, the Dread Pirate Roberts was a role that had been handed down from one man to the next, he said. In this telling, the current Roberts found Silk Road soon after it launched in 2011, identified a flaw in its Bitcoin handling, earned the trust of the site’s owner by helping him fix it, and eventually became a business partner who finally bought out the original owner.

Whatever the truth of this origin story, a good Dread Pirate Roberts never wants to be the last Dread Pirate Roberts. He knows when he’s been in the job too long—and he gets out before he loses his edge. If the feds are right, however, Ulbricht was actually making sloppy mistakes from the start. And it didn’t take technical back doors to find him; it just took a lot of solid detective work, some subpoenas, and a search engine.

As for what comes next for Ulbricht, his backers have already begun spinning out elaborate scenarios. One popular thread in the Silk Road sub-Reddit today offers the wild suggestion that jury nullification could keep him Ulbricht out of prison even if the evidence goes against him. But among most Silk Road users, the concern has been more personal: could the feds be coming after me?

Which, after two years of being taunted by Silk Road and its operator, is exactly what the feds want them to think.

Ready to start your Bitcoin journey?

BTCX is Sweden's first Bitcoin exchange. With us, you can buy bitcoin quickly and securely. Experience safety and simplicity when investing in the currency of the future!